Gli Ultimi Prodotti

-

In offerta!

Abbigliamento Uomo | Pigiama In Leggerissimo Jersey Di Puro Cotone | Julipet

€ 193.38€ 76.44 Scegli -

In offerta!

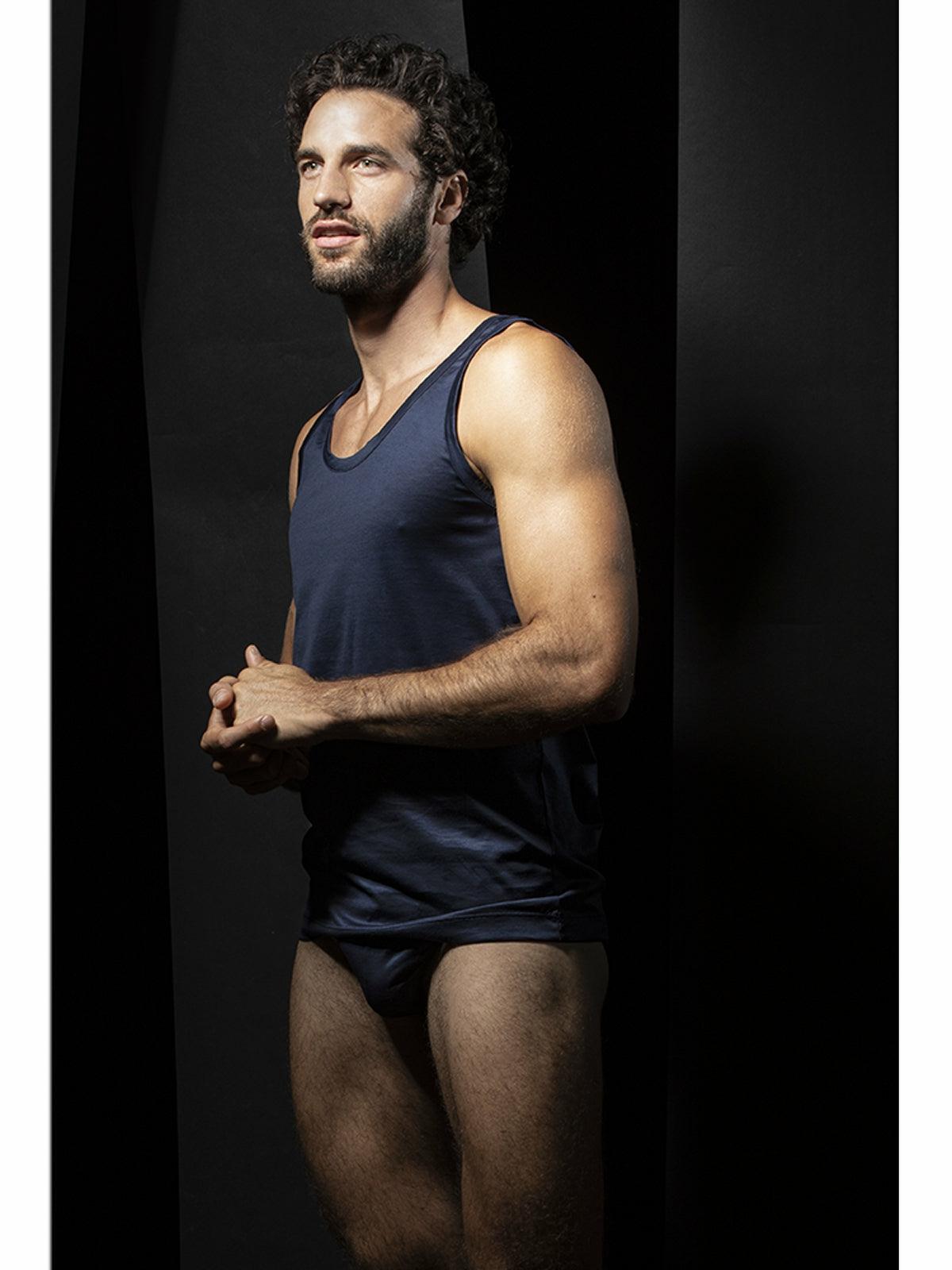

Canotte Uomo | Canottiera In Jersey Di Puro Cotone Mercerizzato E Gasato Blu | Julipet

€ 72.80€ 44.59 Scegli -

In offerta!

Abbigliamento Uomo | Pigiama In Caldo Jacquard Di Cotone | Julipet

€ 185.64€ 76.44 Scegli -

In offerta!

Abbigliamento Uomo | Pigiama In Caldo Tessuto Milano Fantasia Tartan | Julipet

€ 139.23€ 76.44 Scegli

Prodotti Calda

-

In offerta!

Camicie Da Notte Uomo | Camicia Da Notte Artist Edition, In Caldo Interlock Di Puro Cotone | Julipet

€ 146.97€ 76.44 Scegli -

In offerta!

Abbigliamento Uomo | Pigiama In Traspirante Jersey Di Puro Cotone S/Z | Julipet

€ 108.93€ 50.96 Scegli -

In offerta!

Intimo Uomo | Maglietta In Pura Lana Merino | Julipet

€ 123.76€ 76.44 Scegli -

In offerta!

Abbigliamento Uomo | Pigiama In Interlock Stampato Di Puro Cotone | Julipet

€ 124.49€ 64.61 Scegli